Judge Compares Nordstrom’s IP Holding Company State Tax Play to Maligned Basketball Strategy

The counsel for Nordstrom must have known that things were not going to go their way when the opinion’s opening paragraph analogized their client’s “intellectual property holding company” (”IPHC”) tax planning to the historically successful, yet infamous, “four corner’s offense.”

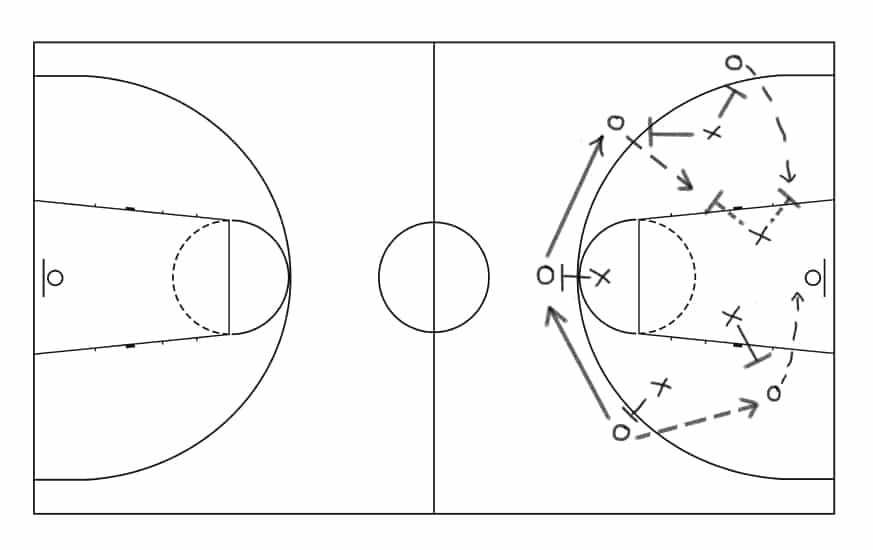

The Four Corner’s Offense

To understand how the analogy works, it is first helpful to take a quick look back at the history of the four corners offense.

This style of offense was a particularly successful basketball strategy devised by John McClendon, a protégé of Dr. James Naismith (the inventor of basketball).[2]

As the Maryland Court of Appeals stated, the “[four corners offense] involved a series of passes among team members that seemingly did not advance the ultimate purpose of putting the ball in the hoop, but had the separate purpose of depriving the opposing team of possession of the ball.”[3] The team would only shoot if it could get a lay-up or other high-percentage shot.

At its peak, the strategy was employed by the legendary University of North Carolina (”UNC”) college basketball coach Dean Smith. UNC’s 1981-82 team, which included future NBA Hall of Famers Michael Jordan and James Worthy, utilized the strategy during its NCAA championship run. [4]

Sound great right? It lead to championships for its user (i.e., the taxpayer in this analogy). Well, not so fast. Basketball fans hated it because the strategy seemed to violate the spirit of the game by turning a match into a game of keep-away.

Several years later, the NCAA introduced the shot clock in order to speed up games and reduce the effectiveness of the four corners offense.[5]

How does Nordstrom’s IPHC planning resemble Jordan and Worthy moving the ball around the court?

As Judge McDonald stated, Nordstrom’s IPHC planning “involved a series of transactions passing licensing rights between related corporations and that was motivated by a desire, not to directly enhance corporate profits, but to keep a portion of those profits out of the hands of state tax collectors.” [6]

So Nordstrom’s profits were essentially equivalent to a basketball in the four corners offense analogy. This left the state tax collectors as the ones chasing the ball.

How did Nordstrom’s IPHC planning play keep away with Maryland?

Nordstrom’s parent company, a Delaware corporation, is headquartered in Seattle, Washington. During the time period relevant to the case, Nordstrom operated stores in 27 states, including four department stores, two discount stores, and one distribution center in Maryland.[7]

Prior to the planning, Nordstrom filed Maryland tax returns and paid Maryland corporate income taxes.

In a series of transaction steps spanning several years in the late 1990’s, Nordstrom’s parent (Nordstrom, Inc.) transferred its intellectual property (i.e., trademarks) to a newly formed Colorado corporation, NIHC.[8] That subsidiary then transferred a license agreement back to Nordstrom Inc. As a result of the transactions, Nordstrom Inc. ending up paying its own subsidiary a royalty, which reduced Nordstrom Inc.’s profits on a stand-alone basis.

Each step in Nordstrom’s plan was carried out by executing legal documents, but Nordstrom’s operations did not change in any material way.[9]

Federal and Maryland Tax Treatment

Federal Treatment

For federal income tax purposes, the Nordstrom corporations involved in the IPHC planning were all part of the same consolidated group. The transfer of the license agreement to Nordstrom Inc. was a taxable dividend, which triggered approximately $2.8 billion of total gain to NIHC. The transactions also created amortizable basis approximately equal to the total gain.[10]

Under the federal consolidated return regulations, NIHCs gain was deferred and recognized over 15 years. But, the gain was offset in each year by NIHC’s amortization of the license. As a result, the gain and amortization expense offset and the transactions had no material effect on Nordstrom’s federal taxable income.

Similarly, the royalty payment between Nordstrom Inc. and NIHC resulted in no net taxable income for federal income tax purposes. [11]

Maryland Tax Treatment

For state tax purposes, Nordstrom took the position that NIHC was not subject to Maryland tax since it did not have a physical presence in Maryland. Nordstrom, Inc. took the position that the royalties paid to NIHC were deductible in calculating its Maryland taxable income. As a result, Nordstrom’s IPHC planning lead to approximately two million dollars in Maryland tax savings for the 2002 and 2003 tax years.[12]

Or in terms of the four corners offense analogy, the ball (i.e., profits) had been moved to the opposite corner, out of reach of the defender (i.e., the Maryland state comptroller). [13]

The Narrow Issue before the Maryland Court of Appeals

This cased based bounced up and down through the Maryland Tax Court, Circuit Court for Baltimore County, and the Special Court of Appeals before finally finding its way on the Court of Appeals docket.

Before reaching the Court of Appeals, the Tax Court considered three issues (i) whether the US Constitution prevented the Comptroller from taxing gain recognized in Nordstrom’s IPHC planning (i.e., was there nexus); (ii) whether the gain was taxable in Maryland; and (iii) whether Maryland’s separate reporting requirement prevented Maryland from taxing the gain reported for the 2002 and 2003 tax years?

The Maryland Comptroller had prevailed at the lower levels on the first two issue but not the last issue. Because of the procedural posture from decisions in the lower courts, the Court of Appeals concluded that Nordstrom had only preserved the third issue.[14]

Therefore, unlike the Court’s recent opinion in Gore, the Maryland Court of Appeals did not address the US Constitutional question (i.e., whether the intellectual property holding company had nexus with Maryland).[15]

Nordstrom’s Half-Court Shot

On its Maryland tax returns, NIHC had been deferring the gain from the 1999 distribution of the license agreement and recognizing the gain of 15 years, which follows the federal tax treatment.

When the Comptroller challenged Nordstrom’s planning, Nordstrom argued that NIHC had improperly deferred the gain on the distribution of the licensing agreement. Nordstrom argued that NIHC should have included all of the gain on its tax return for tax year that included the distribution date, which was 1999. Conveniently for Nordstrom and NIHC, the 1999 tax year was outside of the statute of limitations and therefore the gain could not be taxed by Maryland. Although the Court did not explain the consequences of reaching such a conclusion, presumably eliminating the deferred gain on each 2002 and 2003 tax returns would resulted in eliminating all of NIHCs income.[16]

The Circuit Court agreed with this argument, but the Special Court of Appeals did not. The Special Court of Appeals reasoned that since the taxpayer did not file an amended return to change its position, Nordstrom was stuck with how it reported the income on its Maryland tax returns.

The Maryland Court of Appeal’s Holding

Although the opinion is more than 20 pages long, the holding appears to be somewhat limited. The Court of Appeals affirmed the Court of Special Appeals decision that NIHC’s income could be attributed to Nordstrom because NIHC lacked economic substance apart from its parent, Nordstrom Inc. The Court concluded that Maryland’s separate reporting requirement did not prevent the Court of Special Appeals’ holding.

The Court of Appeals declined to consider the possibility that Nordstrom and NIHC had improperly reported the income under the federal rules (i.e., the $2.8 billion of gain should have been reported on NIHC’s 1999 return). The Court of Appeals decided the case based upon how Nordstrom and NIHC had original filed their tax returns. The Court noted that NIHC did not file an amended return or file a “pro forma” return to adopt a different accounting of the transaction prior to the running of the statute of limitations. As a result, the taxpayer had not given the court any basis for considering the argument.

Conclusion

Although the case involved IPHC state tax planning that is conceptually similar to that in Gore, the Court of Appeals holding in this case is somewhat limited due to the case’s procedural posture. Nevertheless, the ultimate conclusion of this case marks another victory for the Maryland Comptroller. After the Comptrollers’ victories in NIHC, Gore, and SYL[17], taxpayers should carefully consider whether their state tax planning is susceptible to a general economic substance challenge in Maryland.

[1] No. 63, September Term 2013. Case No. 03-C-10-9151. (“Slip Opinion”)

[2] Ironically, McClendon is also sometimes credited with inventing the “fast-break.”

[3] Slip Opinion at 1. For a sample, see this YouTube video of the four corners offense by Phil Ford of UNC, arguably the best at running the offense.

[4] See Wikipedia – 1981-82 UNC Team and this 1982 New York Times article by Gordon S White Jr entitled: Boring, But it Worked.

[5] See Wikipedia – Shot Clock.

[6] Slip Opinion at 1.

[7] Slip Opinion at 3-4.

[8] Nordstrom’s planning actually utilized several Colorado corporations (NTN, Inc.; NIHC, Inc.; and N2HC, Inc.). However, NIHC was the chief subsidiary in Nordstrom’s IPHC tax planning. See Slip Opinion at 4-5.

[9] The Court of Appeals noted that all of the officers of NIHC and N2HC were officers or employees of Nordstrom. Both corporations occupied rented office space in Portland, Oregon, but the operating expenses of the affiliates were relatively minimal. There was no or little income and expense aside from the income or expense created by the IPHC tax planning. Slip Opinion at 5.

[10] Slip Opinion at 8. The amortizable basis was in one of the other Colorado subsidiaries created for Nordstrom’s IPHC tax planning. Nevertheless, for federal income tax purposes, the Colorado subsidiaries were part of the same consolidated group so there was no net effect on Nordstrom’s federal taxable income.

[11] As this section explains, this tax planning did not have a material impact on Nordstrom’s federal taxable income. However, for federal income tax purposes, companies employ an analogous strategy using offshore intellectual property holding companies. In those cases, companies will attempt to move profits offshore out of the reach of the US federal government by moving their intellectual property offshore. See this Robert Wood article on Forbes.com for a summary of this type of planning.

[12] Nordstrom’s IPHC planning saved Nordstrom additional amounts in each tax year in which it continued to shift income from Nordstrom, Inc. to NIHC by paying the intercompany royalty. Note that Nordstrom is not the only company to implement IPHC planning. In fact, a number of companies have carried out IPHC planning strategies to minimize state tax bills and federal tax bills. However, some of these plans have been undone by state court doctrines, usually economic substance.

[13] In 2004, the Maryland legislature passed an intercompany add-back statute to reduce IPHC tax planning. The statute applies to tax years beginning after 2003, so it did not apply in the NIHC case. See Md. Code Unann. Tax-Gen. section 10-306.1 (Md. Gen. Assembly 2014) (providing that companies must add otherwise deductible interest and intangible expenses paid to related entities back to their taxable income base, unless an exception applies).

[14] The Court of Appeal’s opinion on this matter spans several pages and is far more detailed. This was a point of contention that was litigated before the Court of Appeals. Generally, the more difficult question is whether or not the US Constitution prevents taxation by the state taxing authority. However, the Court of Appeals did not analyze this issue because the Court concluded that it was not an issue before the Court. Whether or not the US Constitution prevents taxation was litigated recently in the Gore case. Gore Enterprises Holding, Inc. v. Comptroller of the Treasury, No. 36, September Term 2013 (March 2014). Gore presented another case of IPHC tax planning. In that case, the Court of Appeals held that the taxpayer had sufficient nexus with Maryland.

[16] Based upon the facts in the Court of Appeals opinion, the $2.8 billion gain would have been recognized in 1999, which was outside the reach of the Maryland Comptroller. However, the $186 million amortization per year ($2.8 billion/15 years) would have offset most of the $198 million and $212 million royalty payments for 2002 and 2003, respectively. For Nordstrom, this would have eliminated the downside if the Court of Appeals ultimately concluded that NIHC’s income was subject to taxation in Maryland.

[17] Comptroller of Maryland v. SYL, Inc., 375 Md. 78, 825 A.2d 399 (2003).