Taxpayers often have a large number of questions and misconceptions about what happens in an IRS field examination of their individual income tax return. This post provides a summary of the steps in the examination process. In addition, this post discusses some of the key procedural concepts that taxpayers need to keep in mind when facing an IRS examination. Finally, the post will provide a summary of potential avenues to challenge proposed adjustments in the IRS examination report.

Overview of Life Cycle of IRS Examination

The IRS examination process has a number of steps, and it takes a lot of effort by both the taxpayer and the IRS to complete an income tax examination.

Here is a list of steps in an IRS examination in the order in which they generally occur.

- IRS Selects Return for Examination

- Initial Examination Opening Letter and issuance of IDR 1

- Taxpayer Prepares to Respond to IDR 1

- Initial Meeting and/or Document Submission

- IRS Examines Documentation Submitted by Taxpayer

- Additional IDRs May Be Issued

- Additional Documentation and/or Explanations Are Provided

- Draft Examination Report

- Final Report & 30 Day Letter (Marks the end of the IRS Field Examination)

These steps are typically stretched out over a number of months to accommodate a reasonable amount of time to provide documentation and for the IRS examiner to review the records supplied by the taxpayer.

According to the IRS National Taxpayer Advocate’s 2023 report, the average total exam time (hours) for field exams of returns with income between $50,000 and $10,000,000 for FY2022 and FY2023 was 38.2 hours and 37.4 hours respectively.[1] For the same examinations, the average days to audit completion for FY2022 and FY2023 was 317.6 days and 295.2 days, respectively.

After the IRS issues the Final Report and 30-Day Letter, the taxpayer can agree to the report. In this case, the examination adjustments are finalized and the taxpayer must either pay the deficiency or work with IRS collections to enter into a collection alternative.

If the taxpayer disagrees with the report, the taxpayer can file a formal protest to have a hearing with IRS Appeals. Alternatively, if the taxpayer does not respond in 30 days, the IRS will issue a statutory notice of deficiency, which is also known as a “ticket to US Tax Court”. The taxpayer will have 90 days from the date of deficiency to petition to US Tax Court.

In the event that the taxpayer disputes the findings of the IRS examination through IRS Appeals or U.S. Tax Court, the final resolution of the examination could be deferred for an extended period, possibly spanning months or years.

If the taxpayer does not petition Tax Court within 90 days, then the deficiency is assessed (i.e., is entered in the IRS’s records as a debt) and the IRS begins its standard collection procedures.

After the deficiency is assessed, then the taxpayer is at a procedural disadvantage, but the taxpayer may be able to challenge the resulting tax debt through an audit reconsideration or an Offer in Compromise – Doubt as to Liability.

IRS Examination Selection Process

The IRS can select an individual income tax for examination through a number of different IRS “workstreams”.

The IRS’s Annual Data Book does not provide any statistics on how many returns are selected for each examination within each “workstream.” However, IRS internal guidance, IRS press releases, and reports from oversight bodies, such as GAO and TIGTA, provide the broad framework for how the IRS selects returns for examination.

The IRS has various divisions, including Small Business-Self-Employed (SB/SE) and Large Business & International (LB&I). Both divisions have a hand in audit selection, and each division uses different criteria and methods to select returns for examination. An individual can fall within either of these two groups’ crosshairs.

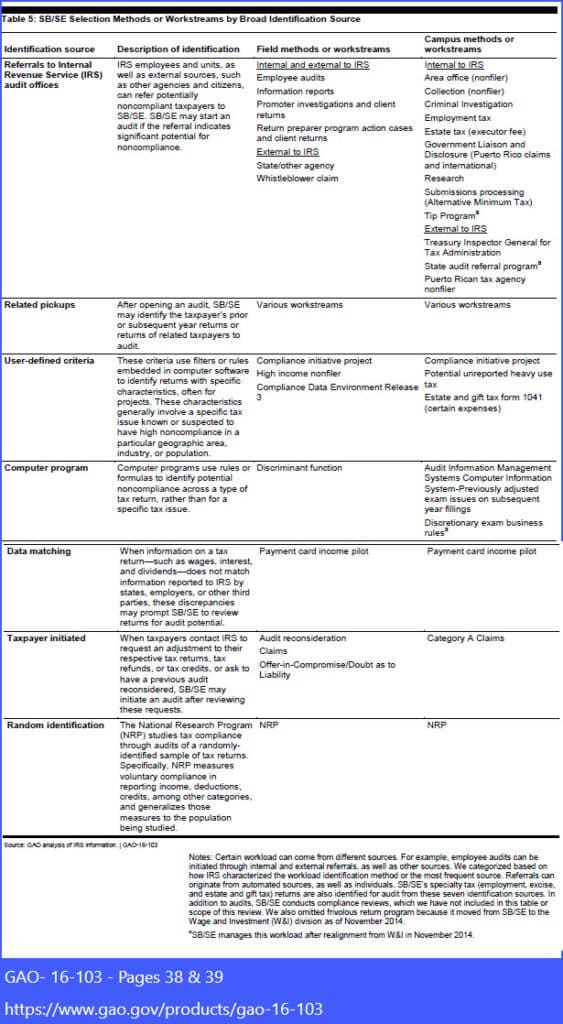

In 2016, GAO provided an overview of SB/SE’s Selection Methods by Broad Identification Source[2], which included:

- Random Identification (i.e., National Research Program (NRP))

- Taxpayer Initiated (e.g., Audit Reconsiderations, Offer In Compromise Doubt as to Liability, Claims)

- Data Matching (e.g., Payment Card Income Pilot)

- Computer Program (e.g., Discriminant Function (DIF Score))

- User-Defined Criteria (e.g., Compliance Initiative Project; High Income Nonfiler, etc);

- Related Pickups (e.g., returns identified during a current exam, including prior or subsequent year returns and/or related party returns)

- Referrals to IRS audit offices from internal and external sources (e.g., IRS Criminal Investigation, Whistleblower, Promotor Investigation, State/Other Agency)

LB&I on the other hand, as the name suggests, focuses more on large businesses than individuals. Nevertheless, LB&I creates campaigns, which are projects focused on a specific compliance-related issues.

LB&I provides a list of active campaigns on the IRS website. Current active campaigns include:

- High Income Non-filers;

- Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) Filing Accuracy;

- Virtual Currency;

- Expatriation of Individuals;

- Foreign Earned Income Exclusion Campaign, and

- a number of others. See Large Business and International active campaigns.

If asked, the IRS revenue agent will generally explain why the return was selected for examination. The explanation can provide some insight into the focus and anticipated scope of the examination. However, the revenue agent is not bound by these initial areas of interest; the Revenue Agent has broad discretion once a return is under examination.

However, the selection does not necessarily mean that there is an issue with the return. According to the 2023 National Taxpayer Advocate Annual Report to Congress, the rate of audits resulting in “no change” for FY2022 and FY 2023 was 13.1%.[3]

Key Concepts: Authority and Scope of an Examination; Authority to Assess

IRC § 6001 requires taxpayers to maintain records in sufficient detail to enable the preparation of an accurate tax return.

IRC § 7602 provides the IRS with broad authority to examine a taxpayer’s records for the purposes of ascertaining the correctness of any return. It also provides the IRS with authority to summon a taxpayer or any other person to appear; to produce books and records; and to give testimony under oath.

While this power is broad, the IRS’s authority to make adjustments to a taxpayer’s income tax liability is limited by the statute of limitations set forth in IRC § 6501. Generally, the IRS has three years from the return filing date to adjust a return. However, there are notable exceptions, including the failure to file a return, gross omission, fraud, and the failure to provide the IRS with certain foreign information.[4]

After the IRS examines a return, the IRS is required to provide the taxpayer with a notice of deficiency.[5] The notice of deficiency (CP3219N; “90-day letter”) generally provides an explanation of the adjustments, the amount of the deficiency (i.e., the increase in the tax and associated penalties and interest), the right to challenge the deficiency by petitioning the US Tax Court within 90 days, instruction for filing a petition, and contact information for the IRS office issuing the notice of deficiency.[6]

There are exceptions to this requirement as well, including adjustments to correct “math or clerical errors[7], assessable penalties[8], jeopardy assessments[9], agreement by the taxpayer[10], and a termination assessment[11].

It is possible to receive a notice of deficiency even if you have not filed a return. The IRC provides the IRS with authority to prepare a return for any person that fails to file a return by the due date. This is called a substitute for return (“SFR”). The IRS is authorized to prepare a SFR from its own knowledge (i.e., information provided by third parties) and from such information as it can obtain through testimony or otherwise. Typically the IRS does not make any elections on the taxpayers’ behalf, so the tax is typically higher than if a taxpayer self-prepared the return. If the IRS prepares a SFR, the IRS will issue a notice of deficiency. [12]

Unless one of the exceptions applies, the proposed adjustments in the notice of deficiency are not assessed until the right to petition U.S. Tax Court lapses. Once the assessment is made, the IRS begins its collection notice cycle.[13]

The IRS has established a number of administrative guidelines for IRS personnel to follow during an IRS examination. This guidance can be found in the IRS’s Internal Revenue Manual, Part 4. Examining Process (link to IRM – Part 4). While taxpayers cannot enforce the IRM’s policies against the IRS[14], it can provide the taxpayer with extensive information on what to anticipate in an IRS examination. In addition, the IRS has created a number of IRS Audit Technique Guides over the years for certain issues and industries. See Audit Techniques Guides (ATGs).

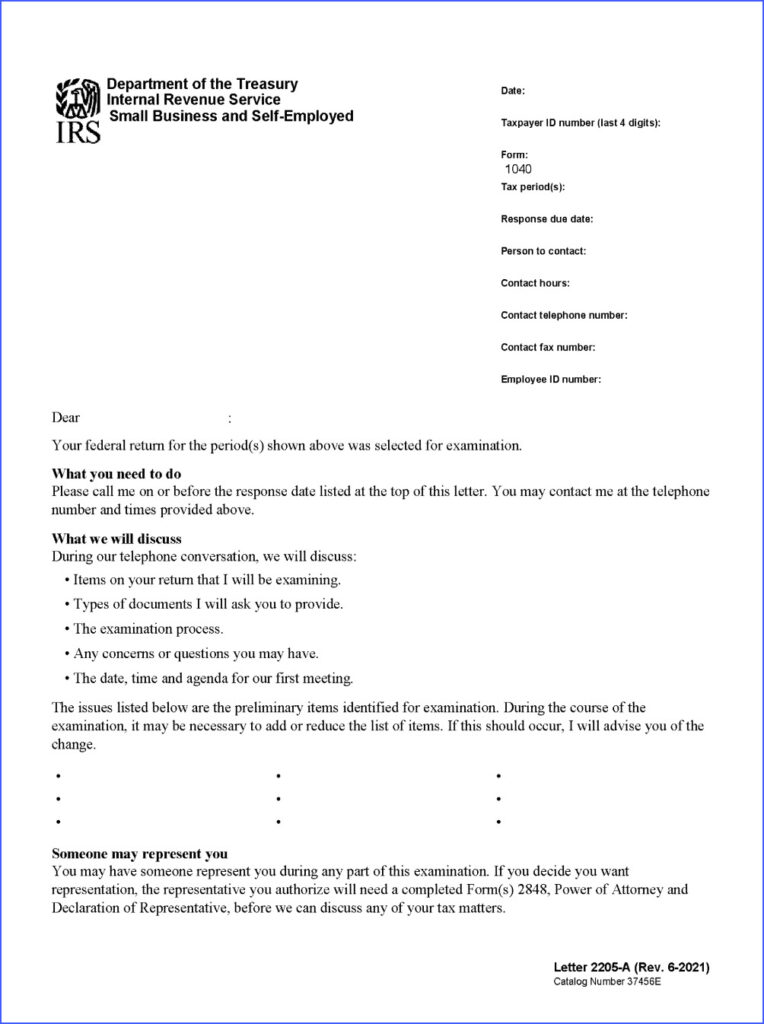

At the outset of an examination, the taxpayer receives an opening letter (i.e., Letter 2205), which will indicate the years that have been selected for examination. The examiner is “expected to continually exercise judgment throughout the examination process to expand or contract the scope as needed.”[15]

“If, during the examination, the scope is expanded to include another tax period(s), the taxpayer must be notified orally or in writing of the expansion. The examiner should: [u]se Letter 5968, Prior or Subsequent Year Pickup, for written notification.” In certain instances, the examiner needs managerial approval to expand or contract the scope of the examination or open up a related taxpayer (e.g., a business owned or controlled by the taxpayer).

Opening Letter & IDR 1

Once the IRS selects an individual’s return for a field examination, the IRS will provide the following notices and letters:

Letter 2205-A (Initial Contact Letter)

Preliminary Issues

In Letter 2205-A, there is typically a section that provides a list of “preliminary items identified in the examination.” These items might have been picked up by IRS computers; they might have been included due to the type of examination (i.e., campaign, specific issue, etc); or an IRS employee might have spotted the issue during a preliminary review of the return.

As the letter notes, the examiner may add or remove items from the list. In that case, the examiner will notify the taxpayer.

Right to Representation

In Letter 2205-A, the IRS notifies the taxpayer that he or she has the right to be represented in the examination. In order to be represented, the taxpayer and the representative must execute Form 2848, Power of Attorney. As discussed below, this need not be an attorney. A “practitioner” authorized to practice before the IRS, such as attorneys, certified public accountants, and enrolled agents, can represent a taxpayer. The practitioner need not have prepared the return(s) under examination.

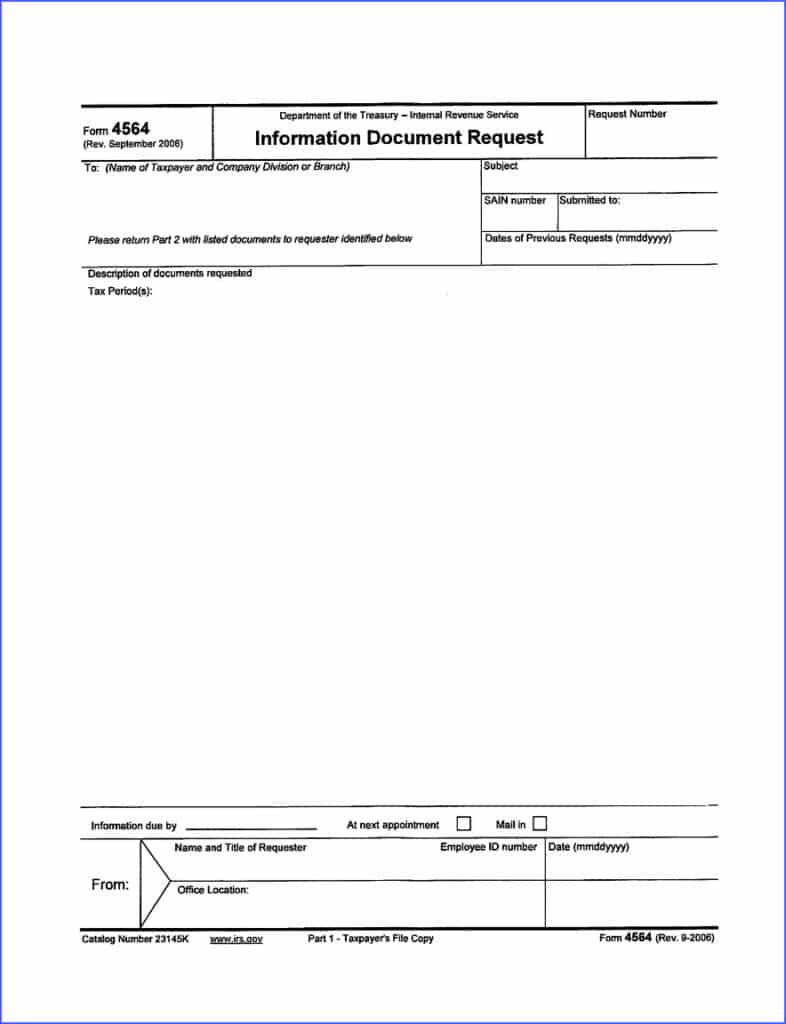

Form 4564, Information Document Request (IDR) 1

- Publication 1, Your Rights As A Taxpayer (link to sample on IRS.gov)

- Notice 609, Privacy Act Notice (link to sample on IRS.gov)

Handling Meetings, Document Requests, and Summons

There is a wide variety of ways to approach an examination. On opposite ends of the spectrum, you have either the scorched earth approach or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, you have the highly accommodating approach.

Under the scorched earth approach, a practitioner will take a hard-lined stance and frequently challenge the examiner’s requests, positions, and conclusions. The practitioner exhausts all options to avoid any adjustments or expansion of the examination.

Under the highly accommodating approach, the representative puts up little to no challenge to the IRS. They seek to resolve discrepancies and issues amicably. They avoid disputes and confrontations, instead focusing on facilitating a smooth and unobtrusive audit process.

Effective representation is an art based on employing an array of soft skills, technical skills, knowledge of tax procedure, and knowledge of substantive tax code provisions. An effective advocate knows when to selectively push back (firmly, yet politely), when to yield on an issue or item, when to accommodate the revenue agent, and when to advocate for a different result.

Responding to IDRs

The taxpayer (or his representative) is best served by reviewing the IDR carefully along with the taxpayer’s tax return. It is important to understand exactly what documents and information the IRS is requesting. The documents and information should be collected from the taxpayer and potentially from related parties (i.e., tax return preparer, bank, investment firm, etc).

Many IDRs are overbroad (i.e., they ask for unnecessary documentation). This is typically due to the use of stock IDRs without tailoring for the taxpayer’s specific situation. It can be helpful to have an open dialogue with the revenue agent to address the scope and level of detail actually needed for the agent to verify the accuracy of item(s) on the return.

If an IDR deadline cannot be met, the taxpayer should request an extension of time in advance. Most revenue agents will provide requests for extensions so long as it is reasonable, and the statute of limitations is not close to expiring.

The documents should also be carefully organized in a reply to the IDR. The taxpayer should keep a copy of the documents and records supplied to the IRS. The taxpayer should never submit the original documents. The taxpayer should always confirm receipt by the revenue agent (i.e., fax confirmation, mail tracking info, verbal communication, and contemporaneous note to the file).

Interview of Taxpayer

In addition to IDRs, IRS revenue agents use “interviews” to help gather information.[16]

During the initial phase of a civil IRS examination, a revenue agent typically likes to interview the taxpayer to “gain an understanding of the taxpayer’s overall financial picture, the business history and operations, and an overview of the taxpayer’s recordkeeping practices.”[17] At the earliest stage, the revenue agent is typically looking to understand how to plan the examination.

The IRS’s IRM correctly observes that “an IRS audit is often a once-in-a lifetime experience for the taxpayer, and therefore the taxpayer may be tense or nervous” in an interview.[18]

Fortunately for taxpayers, unless the IRS has issued a summons for the taxpayer’s testimony, the IRS cannot force a taxpayer to sit for an interview, and a taxpayer has the right to representation at any time during the examination.[19]

Once a taxpayer is represented, the IRS revenue agent must communicate with the taxpayer’s representative and should not speak with the taxpayer.

The IRS’s IRM provides that an examiner” may interview the taxpayer’s representative without the taxpayer present if the representative has first-hand knowledge of the taxpayer’s business, business practices, bookkeeping methods, accounting practices, and daily operations.”[20]

IRC 7521(c) states that an examiner cannot require a taxpayer who has obtained representation to accompany the representative to an examination interview (absent an administrative summons).

Even in the middle of an interview, the taxpayer can invoke this right. During an interview, “if a taxpayer clearly states…that they wish to consult with an attorney, certified public accountant, enrolled agent, enrolled actuary, or any other person permitted to represent the taxpayer before the IRS, the interview must be suspended regardless of whether the taxpayer may have answered one or more questions.”[21]

Practically speaking, in most civil examinations, a taxpayer may be able to avoid sitting for an interview. In most cases, the IRS revenue agent is more focused on completing their examination and, if the examination can be completed without direct testimony, then the agent usually does not push for an interview with the taxpayer.

However, an IRS examiner may initiate “By-Pass” procedures if the taxpayer’s representative “impedes or delays the examination by failing to promptly submit the taxpayer’s records or information requested by the examiner, failing to keep scheduled appointments, or failing to return telephone calls and written correspondence.”[22] The use of the “By-Pass” procedures merely allows the IRS to contact the taxpayer. Nevertheless, the taxpayer still has a right to representation.

The IRM notes that “[a]n administrative summons should be issued if the taxpayer abuses this process through repeated delays or suspensions of interviews.”[23]

Third Party Contacts

If after requesting a document or information from the taxpayer (i.e., on an IDR) and, the taxpayer is unable or unwilling to provide the information, then the IRS can contact third parties to obtain the documents or information.[24]

However, IRC § 7602(c)(1) requires that the IRS give the taxpayer notice before contacting third parties (e.g., banks, customers, employers, banks, etc). The notice is typically valid for 1 year and it must be given 45 days in advance of the contact.

This allows the taxpayer time to attempt to find alternative means to provide the information triggering the notice.

In the past, the IRS used a blanket notification in Publication 1. However, after a change to the law and various court losses, IRS employees were told to issue Letter 3164, Third Party Contact, to fulfill the statutory notice requirement.

After the 45-day period is over, the IRS then issues Letter 1995 to the third party.

Summons

If a taxpayer does not provide all of the information requested in an IDR or refuses to sit for an interview, then the IRS may use its broad authority to summons information from the taxpayer or from a third party.[25]

As noted above, IRC § 7602 provides the IRS with the authority to summon a taxpayer’s books and records or demand testimony under oath. The IRS does not need the approval by a court for its use (except in the case of a John Doe summons).

Generally, this authority allows the IRS to issue a summons to any person having information that “may be relevant” to its investigation. In the context of an examination, this allows the IRS to demand information necessary to determine the accuracy of a return.

However, an IRS summons, may only require the production of existing records.[26] Thus, “[a] summons can only require a witness to appear on a given date to give testimony and to bring existing books, papers, and records. A summons cannot require a witness to prepare or create documents, including tax returns that are not currently in existence”. [27]

A taxpayer can challenge a summons in federal district court based upon the standard set forth in U.S. v. Powell, 379 U.S. 48 (1964).

If the recipient of the summons does not respond, then the IRS can bring suit in federal district court to compel compliance with the summons.[28]

Recording Keeping & Burden of Proof in An IRS Examination

In an IRS examination, taxpayers often ask: what is the IRS’s burden before making an adjustment to the taxpayer’s self-reported income and expense (i.e., the income and expense on the taxpayer’s income tax return)? Many taxpayers are under the impression that the IRS must prove the taxpayer’s position is incorrect. Practically, it is usually the taxpayer, not the IRS, that bears the burden of proof in an examination.

IRC § 6001 requires taxpayers to maintain records in sufficient detail to enable the preparation of an accurate tax return.

IRC § 7602 authorizes the IRS to examine a taxpayer’s books and records to “[f]or the purpose of ascertaining the correctness of any return.”

Examiners are instructed to “pursue an examination to a point where a reasonable determination of the correct tax liability can be made.”[29]

“After all the facts have been gathered through taxpayer interviews; examination of the books, records and supporting documents; interviews with third parties; and, having researched questionable items, the examiner has all the information to be considered in resolving the issues. At this point the examiner will use their professional judgement in considering all the information to arrive at a conclusion.”[30]

Thus after the taxpayer provides the agent with the requested information, the IRS agent makes a determination on a specific issue.

IRS’s Approach to Examining And Adjusting Income

The IRS’s process for examining a taxpayer’s income depends on whether the IRS agent is examining a “business” return or a “nonbusiness” return. In both cases, the IRS starts with “minimum income probes”.[31] However, the IRS typically performs more procedures designed to validate the income reported on a business return.

A nonbusiness return is an “individual tax return[] with no attached business schedule(s); i.e., no Schedule C, Profit or Loss from Business (Sole Proprietorship) or Schedule F, Profit or Loss from Farming.”[32]

For nonbusiness returns, the IRS agent will attempt to reconcile all data the IRS has received from 3rd parties (i.e., Form 1099-INT, 1099-DIV, etc) to the income reported on the taxpayer’s return. The agent will also likely do an analysis of known income and expense data to determine whether there is an indication of a potential understatement of taxable income (i.e., does it appear that the taxpayer is living beyond their means). If these types of analyses do not show any issues, then the IRS agent may end their inquiry. However, if there appears to be a discrepancy (i..e, a “material imbalance”) then the agent may ask for additional information and perform additional procedures.

With respect to a business return, the IRS revenue agent will also typically request a tour of the business, review the business’s internal controls, test gross receipts, perform a bank analysis, review business rations, and look for e-commerce/internet businesses.[33]

If the taxpayer’s self-reported income cannot be reconciled to the taxpayer’s books, then the IRS revenue agent will perform a bank deposit analysis. The bank deposit analysis is designed to reconstruct a taxpayer’s gross income. After the IRS reconstructs a taxpayer’s income, the taxpayer is responsible for proving that the IRS’s results under the bank deposit method was unfair or inaccurate. Under this analysis, the IRS presumes that all deposited money into a taxpayer’s bank account is taxable unless the taxpayer

shows that particular deposits are nontaxable or were previously reported as income.

Taxpayers Bear the Burden of Proof for Deductions

In many U.S. Tax Court opinions, you will find this quote or a similar quote:

“Deductions are a matter of legislative grace, and a taxpayer bears the burden of proving entitlement to any claimed deductions. Rule 142(a)(1); INDOPCO, Inc. v. Commissioner, 503 U.S. 79, 84 (1992). A taxpayer claiming a deduction on a federal income tax return must demonstrate that the deduction is allowable pursuant to some statutory provision and must substantiate the deduction by maintaining and producing records sufficient to enable the Commissioner to determine the taxpayer’s correct tax liability. § 6001; Higbee v. Commissioner, 116 T.C. 438, 440 (2001); Treas. Reg. § 1.6001-1(a).”

Johnson v Commissioner, 160 T.C. No. 2 (2023).

In an examination, this means that if an IRS revenue agent makes an inquiry into an individual deduction or line item, the taxpayer must provide substantiation for the individual deduction or the line item. In addition, the taxpayer must show that the US tax code allows for such a deduction.

In the case of a business expense, the taxpayer needs to show that (i) the expense was ordinary and necessary for the business (see IRC § 162); and (ii) the expense was paid or incurred during the tax year in question.

In many cases, the IRS makes an adjustment because the taxpayer cannot fully substantiate an expense (i.e., the taxpayer lacks documentation, inconsistent information is provided, etc). With respect to business expenses, it is common for the IRS to disallow deductions because they are deemed to be personal expenses rather than ordinary and necessary for the production of business income.

Cohan Rule

Under the Cohan rule, a court may estimate the amount of an expense if the taxpayer cannot substantiate the precise amount. However, the taxpayer must (i) prove that he has paid or incurred a deductible expense and (ii) provide a credible basis for the court to estimate the expense.

Therefore, the taxpayer must come forward with credible evidence to allow the court to estimate the expense.

For example, if the taxpayer does not have detailed receipts for shipping expenses, then the taxpayer may be able to prove that certain products were shipped to customers. In addition, the taxpayer must provide a credible basis for an examiner (or a court) to estimate the shipping costs based upon the known shipping data (i.e., delivery company, type of delivery service, origin and destination of shipments, delivery rates for the given tax year, etc). As a basis for such shipping expenses, the taxpayer could provide customer purchase orders, invoices, contracts, etc. that contain shipping data. While these documents may only provide partial actual expense information, they could provide objective data (i.e., a credible basis) for a reasonable estimate of the cost of such shipments.

Law Demands A Higher Level of Proof For Certain Deductions & Credits

For certain types of deductions and credits, the IRC requires a different and higher level of proof for expenses that are otherwise deductible.

Specifically, section 274(d) prescribes strict substantiation requirements for certain categories of expenses, including travel and listed property (i.e., passenger automobile). These elevated substantiation requirements supersede the Cohan Rule.

Related Treasury regulations provide in relevant part that “adequate records” generally consist of an account book, a diary, a log, a statement of expense, trip sheets, or a similar record, made at or near the time of the expenditure or use, along with supporting documentary evidence.

The log and records are meant to provide the date of the expenditure, the location and purpose of the business meal or event, and attendees and their business relationship to the taxpayer (i.e., how does the meeting help the taxpayer’s business).

Taxpayers should take great care in keeping a log or creating a log from records (i.e., receipts, business calendar, emails, bank and credit card statements, etc.). Inconsistencies in the log and supporting records can significantly undermine a log’s reliability.

Similarly, IRC § 170 imposes additional recordkeeping requirements for those who claim a deduction for charitable contributions. See generally IRS Publication 526, Charitable Contributions. For example, non-cash contributions larger than $250 made to a qualified charitable organization are not tax deductible unless the donee organization supplied the donor (i.e., the taxpayer) with a Contemporaneous Written Acknowledgment (CWA). See 4.19.12.10.2.1.1.2 (12-06-2023), Deduction Criteria. For non-cash charitable contributions greater than $5,000, the taxpayer must obtain a qualified written appraisal.

In the context of an examination, the IRS revenue agent will verify that such additional recordkeeping requirements have been met.

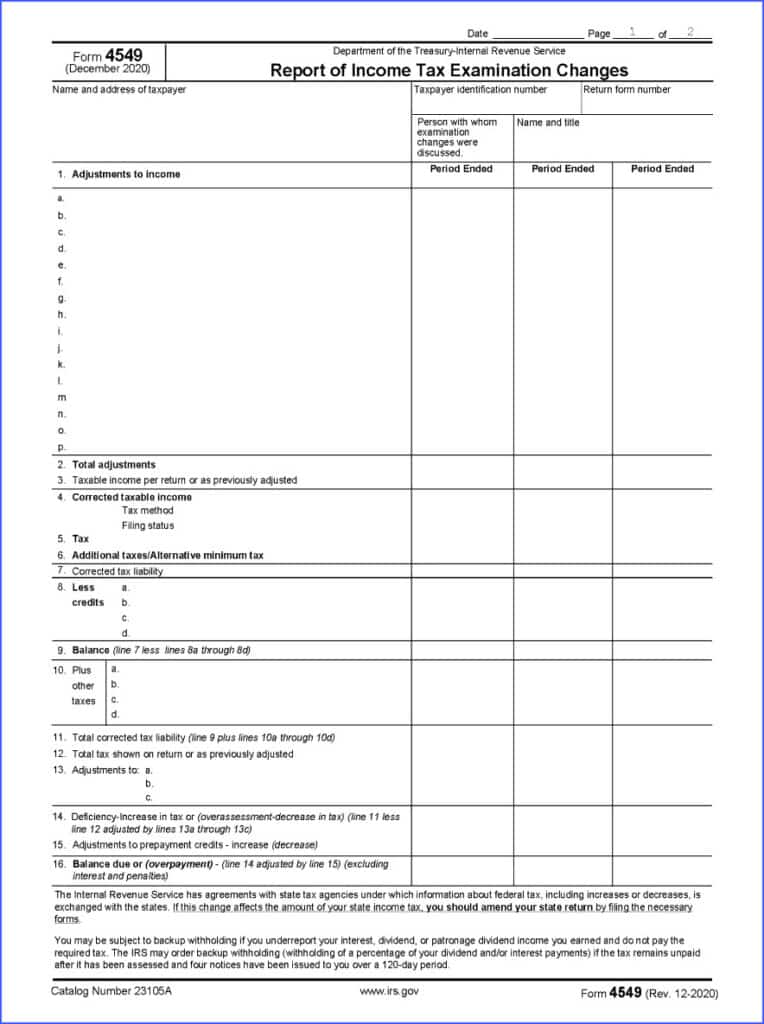

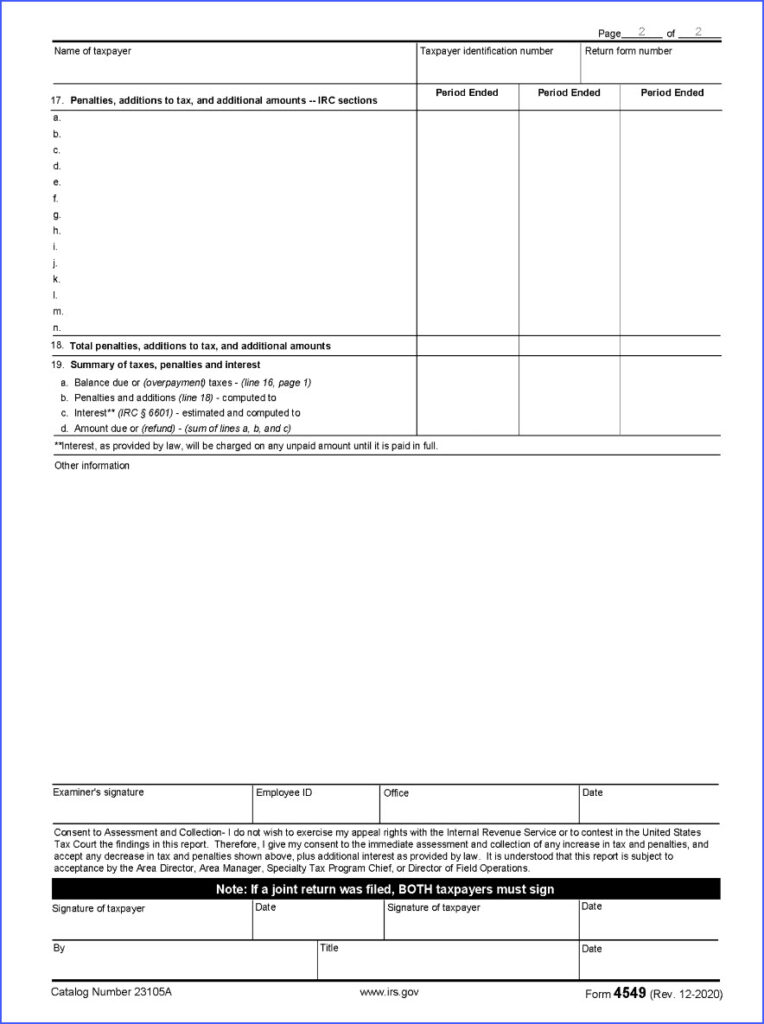

Examination Report – Form 4549, Lead Sheets, and Calculations

At the conclusion of an IRS field examination, the IRS revenue agent will usually issue a Letter 915, Examination Report Transmittal (also known as the “30-Day Letter”); Form 4549, Report of Income Tax Examination Changes; Lead Sheets; and supporting calculations.

Letter 915, Examination Report Transmittal (30-Day Letter)

Letter 915 (“30-Day Letter”) is a very important milestone in the examination life cycle. As discussed below, there are some very important decisions to be made at this point. Some options are lost if the 30-day period lapses without response to the IRS.

The 30-Day Letter generally states that copies of the examination report are enclosed, which shows the changes made to the periods referenced in the letter. The letter states that you can indicate whether you agree or disagree with the changes. The letter gives the taxpayer 30 days to respond.

If you agree, then the letter instructs you to sign, date, and return the copy by the deadline. It also provides instructions on how to pay the deficiency. Alternatively, if you cannot pay, then it points to additional guidance on payment options (i.e., Publication 3498, The Examination Process).

However, if you do not agree, then you can (i) attempt to work with the revenue agent and with the agent’s supervisor to have the report adjusted or (ii) request a conference with IRS Appeals, which requires that you file a formal protest.

If you fail to respond within 30 days, then the IRS sends you a notice of deficiency (i.e., ticket to U.S. Tax Court).

The 30-day period is not imposed by statute. It is possible to request additional time to work with the IRS revenue agent or respond to the letter. However, this should be requested in writing. If possible, obtain the grant of additional time in writing from the IRS or put it in writing by faxing the revenue agent a confirmation after receiving the extension orally (i.e., during a call or a face-to-face meeting).

Form 4549, Report of Income Tax Examination Changes

Form 4549 provides key information regarding the revenue agent’s conclusions. The form is two pages, which are broken down into several key sections. Each page can cover up to three tax years. If there are more than three tax years at issue, more than one Form 4549 may be issued.

The first section provides line-by-line details of the examiner’s proposed adjustments. Each line corresponds with a different adjustment (i.e., increase for omitted income, denial of travel expense, denial of deduction for NOL carryover, etc).

The next section calculates the amount of tax after taking into account the adjustments. The report determines “correct taxable income” by adding the total amount of the adjustments to the amount of taxable income reported on the original tax return. Using the “correct taxable income”, the form then provides the corrected tax liability along with any changes to tax credits.

The form then computes the deficiency by comparing the “corrected tax liability” with the total shown on the original return. The deficiency is the amount of tax that results from the revenue agent’s adjustments. After making an adjustment to prepayment credits, the form provides the balance due, which is at the end of page 1.

Page 2 of Form 4549 then explains the addition of penalties and interest before arriving at the total amount due for each tax year under examination. Penalties and interest are driven by the amount of underpayment of tax.

The most frequent penalties are accuracy-related penalties, late filing penalties, and late payment penalties. Late filing and late penalties are difficult to abate. However, accuracy-related penalties can be eliminated if the taxpayer can show that the taxpayer had reasonable cause.

In many examinations, the Revenue Agent will provide the taxpayer with a draft report. Typically, this includes a draft Form 4549 but not the supporting lead sheets. However, the agent will sometimes share some of the lead sheets. This is helpful to understand the IRS’s position on an issue and the grounds for the proposed adjustment. This becomes particularly important to help the taxpayer or representative know what additional evidence or explanation might be necessary to reach an agreement on an issue.

The final Form 4549 must be scrutinized by the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s representative. Typically, the taxpayer has worked with the agent to explain and successfully resolve potential issues raised by the revenue agent. By this point in the examination, the revenue agent has likely already telegraphed what adjustments are going to be made on the final report. It is important to confirm that the report reflects only issues that could not be successfully resolved.

IRS Lead Sheets & Workpapers

The 30-Day Letter and the Form 4549 are typically accompanied by workpapers providing detailed information on each of the adjustments made on the Form 4549. These supporting documents are usually labeled as “Lead Sheets” or “Workpapers.” Each adjustment typically has its own supporting workpaper. Each workpaper provides:

- the amount of the adjustment,

- the conclusion on the issue,

- facts gathered in the examination that are relied upon for the adjustment,

- a summary of the law underlying the issue,

- Taxpayer’s position; and

- Audit procedures related to the issue.

These documents can show errors in the IRS’s understanding of the facts and analysis of the law. This can be extremely helpful in attempting to resolve the issue with the revenue agent and the agent’s manager.

In the event that it cannot be resolved with the IRS’s field team, then the document can help inform the taxpayer. With information on the IRS’s position, the taxpayer can analyze whether or not the issue should be challenged in IRS Appeals or U.S. Tax Court.

Supporting Calculations

Behind the 30-Day Letter, the Form 4549, and Lead Sheets, the final report will typically contain many pages of calculations. These calculations are incorporated in to the Form 4549 and the lead sheets.

For example, if the IRS increases the amount of self-employment income, then there will be an accompanying increase in self-employment tax. This increase will generate a separate calculation worksheet to provide the details of how the increase in tax was computed.

These computations should also be reviewed for errors.

Beyond the Examination: IRS Appeals or US Tax Court

If you still disagree with the report and you cannot convince the revenue agent to change the report, then you are left with two options before the additional tax is assessed.

The first option is to submit a written protest within 30 days of the letter date to the address on the 30-Day Letter. The final report should provide information on how to draft and submit the protest.

For more information, see IRS Publication 5 here: Publication 5 (Rev. 4-2021) (irs.gov)

Alternatively, if you do not respond to the 30-Day letter, then the IRS will issue notice of deficiency. The deficiency should come with instructions on how to file a petition with U.S. Tax Court (i.e., a petition kit). See https://www.ustaxcourt.gov/resources/forms/Petition_Kit.pdf

If you do not file a petition within the 90 day period beginning on the date of the notice of deficiency, then the IRS will assess the tax, penalties, and interest on the notice of deficiency. Afterward, the IRS will begin its general collection procedures.

Do you need representation?

Navigating an IRS examination can be daunting, but you don’t have to go through it alone. While you can certainly choose to work with your existing tax return preparer, it’s crucial to ensure that your representative thoroughly understands both the intricacies of your tax return and the IRS examination process itself. Not every preparer has the depth of experience required to manage the complexities that may arise during an audit.

It’s also important to consider potential conflicts of interest. Your tax return preparer might be in a position where defending the return could conflict with providing you unbiased, objective advice. This is where bringing in a different tax professional can be highly beneficial. An independent tax professional, who wasn’t involved in preparing your return, can offer a fresh perspective, free from any conflicts, and focus solely on defending your interests.

You don’t necessarily need a tax attorney to guide you through the examination process. The key is to have a professional by your side who has a deep understanding of books and records, as well as extensive experience in dealing with the IRS. Engaging a different tax professional at various stages—whether at the issuance of a draft examination report, a final examination report, or even earlier—can provide strategic advantages. This fresh expertise can be especially valuable in identifying issues, negotiating with the IRS, and ensuring the best possible outcome.

My experience as a CPA, combined with years of assisting taxpayers through IRS examinations, allows me to provide the knowledgeable, strategic representation you need. Whether from the start or at a later stage in the process, having the right professional on your side can make all the difference in protecting your interests and minimizing potential liabilities.

Notes

[1] See National Taxpayer Advocate Annual Report to Congress for 2023, Figure 1.2.3, Type of Audit, Outcomes, and Time to Complete by Income, FYs 2021-2023.

[2] See GAO, IRS RETURN SELECTION: Certain Internal Controls for Audits in the Small Business and Self-Employed Division Should Be Strengthened, Table 5: Selection Methods of Workstreams By Broad Identification Source.

[3] See National Taxpayer Advocate Annual Report to Congress for 2023, Figure 1.2.3, Type of Audit, Outcomes, and Time to Complete by Income, FYs 2021-2023. In addition, according to the most recent IRS Data Book, 50,664 out of the 268,560 examinations closed for individual returns from tax year 2021 resulted with no change. 2023 IRS Data Book, Publication 55-B (Rev. 4-2024), available at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p55b.pdf

[4] For a more in depth discussion statute of limitations on assessment (§ 6501) see the post, [title], [Link]

[5] See IRC § 6212.

[6] See IRC § 6213.

[7] See IRC § 6213(b)(1).

[8] See generally IRC § 6671. “Assessable” penalties are generally those that are due and payable upon notice and demand. Unlike penalties subject to deficiency procedures, assessable penalties carry no rights to a notice prior to an assessment, to Appeals rights (i.e., 30-day letter), or agreement to an assessment form. Thus, taxpayers do not have a right to judicial review prior to assessment, and a taxpayer must pay the tax, seek a refund from the IRS, and file a refund suit in federal district court to obtain judicial review of the merits of the penalty.

[9] See IRC § 6861 (requires a notice with right to petition US Tax Court after the “jeopardy” assessment).

[10] IRC § 6213(d) allows the IRS to assess tax agreed upon by the taxpayer without issuing a notice of deficiency. This is typically done with Form 870, Waiver of Restrictions on Assessment and Collection of Deficiency in Tax and Acceptance of Overassessment.

[11] See IRC § 6851 (authorizing the IRS to immediately assess and collect taxes if it believes that assessing or collecting tax would be jeopardized by delay, such as when a taxpayer is attempting to quickly depart from the U.S. or dispose of assets).

[12] See IRC § 6020(b).

[13] For more on the notice collection cycle, see [name of post] – [link].

[14] “Noncompliance with the manual does not render an action of the IRS invalid… Procedures in the Internal

Revenue Manual are intended to aid in the internal administration of the IRS; they do not confer rights on

taxpayers.” Carlson v. United States, 126 F.3d 915, 922 (7th Cir. 1997); see also Thompson v. Commissioner,140 T.C. 173.

[15] IRM 4.10.2.7.1.2 (09-29-2022), Determining the Scope of an Examination – Current, Prior and Subsequent Years

[16] An “interview” may be a 1 to 2 hour meeting for an exhaustive discussion regarding the taxpayer’s return and all associated topics related to the substance reported in the return (i.e., income, investments, deductions), role of advisors (i.e., tax return preparers, bookkeepers, etc), and prior history with taxing authorities (i.e., prior IRS or state tax examinations, correspondence with IRS, etc). On the other hand, an interview may be a more abbreviated follow-up discussion regarding specific documents or issues raised during the examination.

[17] IRM 4.10.3.4.1.1 (05-03-2023), Initial Interviews.

[18] IRM 4.10.3.4.5 (1)(d)

[19] IRC § 7521(b)(2)

[20] IRM 4.10.3.4.3.1 (05-03-2023), Taxpayer’s Representative.

[21] IRM 4.10.3.4.5.2 (2).

[22] IRM 4.10.3.17.4 (5). See IRM 4.11.55.4, By-Pass of a Representative.

[23] IRM 4.10.3.4.5.2 (5).

[24] See IRC § 7602(c); IRM 4.11.57.2 (10-05-2022), TPC Introduction

[25] In practice, when the IRS is preparing a full bank deposit analysis, the summons authority is used relatively frequently in an examination to request bank statements; images of bank deposits and cancelled checks; and other financial information, particularly when the taxpayer cannot obtain the information directly from the bank.

[26] There are a some exceptions to this general rule, including the IRS may require a handwriting exemplar, and, in certain instances, a taxpayer must produce an English translation of responsive foreign language documents. See e.g., Treas. Reg. § 1.6038A-3(b)(3).

[27] IRM 25.5.4.2(5). Note that a subsequent section in the IRM reiterates, “[b]y issuing an administrative summons, the Service cannot force a taxpayer to create a document, including a Collection Information Statement or a delinquent tax return.” I.R.M., pt. 25.5.4.2.1(1).

[28] See IRC 7402(b) and IRC 7604; see also IRM 5.17.6.22 (11-28-2023), Civil Enforcement.

[29] 4.10.7.3 (01-01-2006), Evaluating Evidence.

[30] See IRM 4.10.7.4 (01-01-2006), Arriving at Conclusions.

[31] See IRM 4.10.4, Examination of Income.

[32] IRM 4.10.4.2.1 (08-09-2011), “Nonbusiness” Returns.

[33] See IRM 4.10.4.3.3 (08-09-2011), Minimum Income Probes: Individual “Business” Returns.